All kinds of figures are circulating about the death toll of the Spanish Flu. Depending on the author, some 10, 20, 50 or even 100 million people died worldwide during the epidemic in 1918-19. All these figures have two things in common, namely that they are very high and they are not usually based on a detailed study of the sources. In other words, they are rough estimates.

In an article published in De Standaard on 20 April 2020 (De ‘moeder aller pandemieën’ die onder de mat geveegd werd, which translates as The ‘mother of all pandemics’ that was swept under the carpet), Marc Reynebeau states that the epidemic of 1918-19 cost the lives of almost 300,000 Belgians. He bases this on the figure of 282,165 deaths mentioned in a master’s thesis (Antwerp University, 2017), where this figure is attributed to André Lambert, who studied the demography of the First World War. This figure is surprising, on the one hand because it is so precise and on the other because it is extremely high, even incredibly high. Research shows that nowhere does Lambert put forward a figure of 282,165 deaths for the Spanish Flu. Lambert only provides a table with the official annual mortality figures (regardless of the cause of death) between 1910 and 1920. This shows that 282,165 is simply the rounded sum of the total number of deaths in Belgium over two years (the sum for the years 1917-18, and moreover not for 1918-19). The figure of 282,165 deaths in the thesis is therefore based on the reasoning that every death in those years, from the youngest baby to the oldest Belgian, was due to the Spanish Flu. Which would mean that no one was killed then by any other disease or military force, or died outside the three brief waves of the epidemic. Of course, this is impossible.

Belgium is hardly ever mentioned in international studies on the Spanish Flu because the historical sources are incomplete and not transparent enough. In the Belgian context, however, the figure of 282,165 deaths from this thesis is already quoted on the Wikipedia page on the Spanish Flu, was used in a website that promotes flu vaccines, and recently it formed the basis of an article in the quality newspaper De Standaard. Such a figure, especially one of this magnitude, will therefore take on a life of its own. Numbers are attractive and easily copied, especially when they are available online. They radiate reliability but do not necessarily reflect reality. In particular, when it comes to epidemics from the past, it seems that the numbers can never be big enough. But the death toll does not have to be so high to have a major social impact, as we now know.

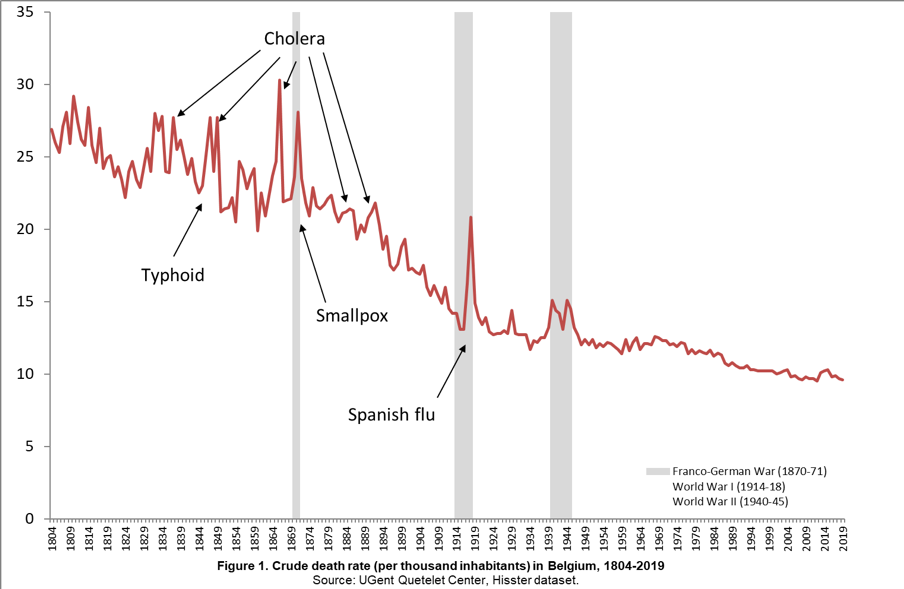

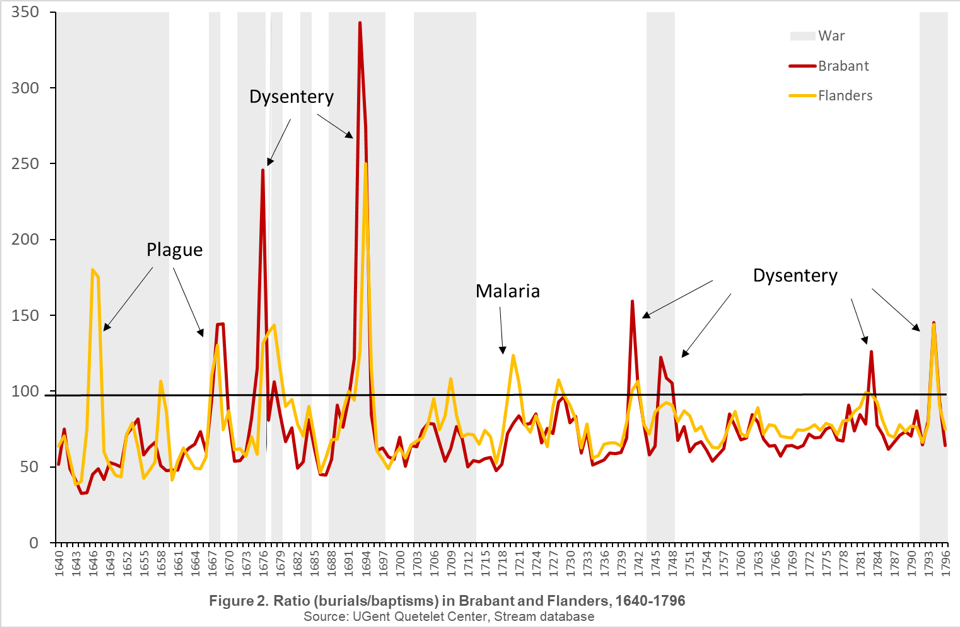

So far, not a single historian has ventured to calculate the number of victims of the Spanish Flu in Belgium. This is due to the fact that the cause of death statistics for the war years have not been preserved and it is therefore difficult to distinguish between deaths caused by war, flu or other diseases. Moreover, the mortality statistics for these years are incomplete: we do not have data for the worst affected municipalities on the war front, those in the Westhoek. Because the data at the national level are incomplete, in recent years there have been several studies on the Spanish Flu conducted at the local level (master’s theses UCLouvain, 2018 and Ghent University, 2005 and 2009). These show that the excess mortality could vary greatly from place to place, but that the mortality in 1918-19 was much higher than before the war almost everywhere. This is also indicated by quantitative analyses based on municipal data from the series of archives Le Mouvement de la Population et de l’Etat Civil (State Archives of Belgium). In comparison with the pre-war mortality figures (about 110,000 deaths annually), the figures in 1918-19 were on average a third higher.

Many European countries have more complete sources to measure the impact of the Spanish Flu. In recent decades, various studies based on historical sources and statistical methodologies have been able to determine more accurate mortality figures. For the Netherlands, these estimates range between 20,000 and 60,000 victims, for France between 230,000 and 360,000, and for England between 150,000 and 280,000. Depending on the scale of the epidemic, the Spanish Flu accounted for 10 to 25 per cent of the total annual mortality in the different countries. Taking into account a correction for under-registration, this means that in Belgium the epidemic claimed about 30,000 victims in the best case scenario and almost 80,000 in the worst case. Contemporaries estimated the mortality figure from the Spanish Flu in our country to be 20,000.

Over the past few months, reports on the corona epidemic have also alerted us to both the benefit and the dangers of numbers. There is a lot of discussion about the method of counting and calculating COVID-19 mortality. In Belgium, the scientific institute Sciensano has a comprehensive counting method: in addition to the COVID deaths in hospitals, it also reports people who died of the disease at home or in a residential care centre, along with any other suspected COVID deaths. Such detailed data help in better mapping the course of the disease, making better predictions and ultimately also avoiding deaths. Unfortunately, this does not make international comparisons any easier. Due to the comprehensive reporting method, the Belgian figures are much higher in relative terms than in other countries. In any event, the basis of our figures is clear. Something that cannot be said of the hallucinatory figure of almost 300,000 Belgian victims of the Spanish Flu.

Sources

- State Archives of Belgium, Le Mouvement de la Population et de l’Etat Civil, 1910-1920.

- Ministère de l’Intérieur, Annuaire Statistique de la Belgique 1915-1919, Brussels.

- Quetelet Center, HISSTER Database, 1910-1920.

Bibliography

- Ansart, Séverine, Camille Pelat, Pierre‐Yves Boelle, Fabrice Carrat, Antoine Flahault, and Alain‐Jacques Valleron. “Mortality burden of the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic in Europe”, Influenza and Other respiratory Viruses 3, no. 3 (2009): 99-106

- Baudhuin, Fernand. Histoire économique de la Belgique, 1914-1939. Brussels: E. Bruylant, 1946, vol. 2.

- Brulart, Benjamin. “La grippe espagnole en Belgique occupée (1918-1919) : analyse épidémiologique et étude de l’imaginaire et de la perception de l’épidémie à travers les carnets de guerre”. PhD. Diss., UCLouvain, 2018.

- De Smet, Saartje. “De Spaanse griep in België”. PhD. Diss., Ghent University, 2005.

- Hendrickx, Laurine. “Onderschat en onbeantwoord. De publieke perceptie van de Spaanse griep in de Belgische context (1918-1930)”. PhD. Diss., Antwerp University, 2017.

- Johnson, Nial Philip Alan Sean, and Mueller Juergen. “Updating the accounts: global mortality of the 1918–1920 ‘Spanish’ influenza pandemic”. Bulletin of the History of Medicine 76, no. 1 (2002): 105–115.

- Lambert, André, “La population de la Belgique dans la guerre 1914-1918”. Lecture for the memorial of WOI organized by de Vlaamse Vereniging voor Demografie and Société Démographique Francophone de Belgique, February 2014. http://adrass.net/WordPress/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/rap1418_final.pdf

- Murray, Christopher J., Alan D. Lopez, Brian Chin, Dennis Feehan, and Kenneth H. Hill. “Estimation of potential global pandemic influenza mortality on the basis of vital registry data from the 1918–20 pandemic: a quantitative analysis”, Lancet 368, no. 9554 (2006): 2211-2218

- Patterson, D.K., and Pyle G.F. “The geography and mortality of the 1918 influenza pandemic”. Bulletin of the History of Medicine 65, no. 1 (1991):4–21.

- Reynebeau, Marc, “De ‘moeder aller pandemieën’ die onder de mat geveegd werd”. De Standaard, 20 April 2020. https://www.standaard.be/cnt/dmf20200419_04927397

- Van Laere, Stefanie, “’Over-leven na de Groote Oorlog’. De demografische gevolgen van de Eerste Wereldoorlog in België in kaart gebracht”. PhD. Diss., Ghent University, 2009.