BELGIUM: THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY ANTI-VAXXER?

DETAILS

Used database:

Date:

Category:

Auteur: Isabelle Devos

At the end of December 2020, Belgium started the vaccination campaign against COVID-19. This is more than two centuries after the very first vaccine was administered. Back then, it concerned smallpox, the only disease for which a vaccine was developed and rolled out on a large scale in Europe as early as the nineteenth century. For other infectious diseases, this did not happen until the 1950s-60s.

Although Belgium was one of the pioneers of smallpox vaccination, it failed to introduce compulsory vaccination against the disease in the nineteenth century, unlike almost all other European countries. It became clear that the information campaign from the start was not enough to overcome the lack of political will and suspicion among the general public in the longer term.

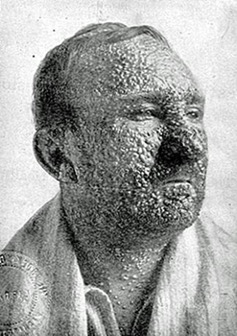

Variola virus

From variolation to vaccination

The forerunner of vaccination, so-called variolation, was introduced to Europe early in the eighteenth century. This technique, which originated in China, consisted of deliberately infecting people by applying a small dose of smallpox (scabs or pus from the sores) through a cut in the arm.

Variolation became known in Europe through, among others, Lady Mary Montagu, wife of the British ambassador in Constantinople, who had learned about it there.

Once a victim of the disease herself, on her return to England she had her daughter inoculated in the presence of several prominent doctors. Many enlightened minds and monarchies, such as in Sweden and Russia, encouraged the use of this new medical technique.

The first variolations in our regions took place on 17 May 1768 in Brussels. The Gazette des Pays-Bas reported on it two days later. Doctors in other cities and rural municipalities soon followed.

Various ordinances were issued under Maria Theresa and Joseph II to prevent the spread of the disease by using variolation. As of September 1768, variolations were only allowed to be administered at a distance of least 200 toises (390 metres) from a built-up area. Violations were punished with a fine of a thousand guilders. In 1788, Joseph II extended the distance to 400 toises and introduced a higher fine.

Meanwhile, opposition to the variolations had grown all over Europe, especially from the clergy and doctors. On the one hand, it was considered interference with God’s work and, on the other, inoculating healthy people was thought to be dangerous.

Vaccination

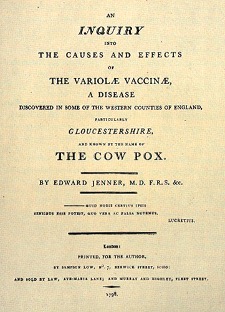

A few decades later, the British country doctor Edward Jenner came up with a new, less risky technique. In 1796, he discovered that milkmaids could get cowpox, but did not get the dangerous human smallpox.

Cowpox was a milder form of the human variant and it made these women immune to smallpox. The inoculation of healthy people with cowpox would protect them for life, according to Jenner.

At the beginning of 1800, the first inoculation with cowpox was administered in Ostend. The first smallpox inoculations, later called vaccination (from the Latin for cow: vacca), were initiated by a number of surgeons and medical societies.

They tried to convince the population of the benefits through popularizing brochures and lectures. Some doctors also offered inoculations free of charge, such as Joseph Kluyskens in Ghent and Louis Vrancken in Antwerp.

Promoting the cowpox inoculation was also an important pillar of the health policy of the enlightened French administration, which continued under the Dutch and Belgian regime. Local vaccination committees were set up for this purpose.

From 1807 onwards, smallpox inoculation became a condition in various places for access to municipal education and poor relief. In 1818, this was extended to the rest of the Low Countries, including a vaccination registration. People could obtain an inoculation free of charge from a doctor.

Outstanding vaccinators were awarded a medal and a small cash premium. However, as there was no compulsory school attendance at the time, a large proportion of the children were not included. Moreover, the inoculation of healthy people aroused a lot of suspicion, which was sometimes religiously motivated.

Compulsory vaccination?

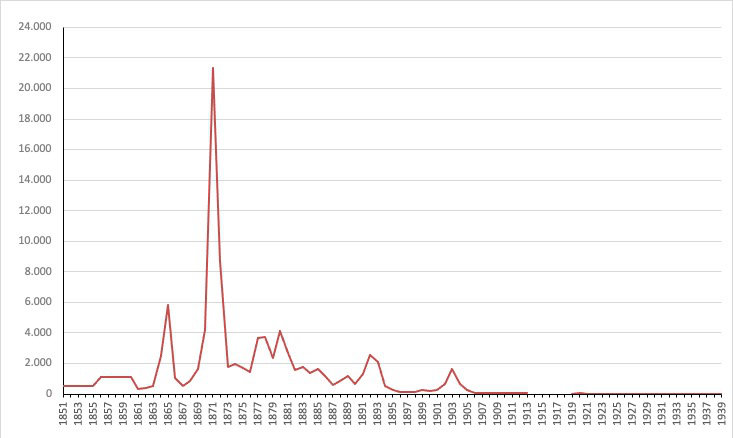

DThe introduction of compulsory vaccination in Europe took place in two phases. Bavaria and Hesse were the first in 1807, quickly followed by other Prussian states, Denmark, Sweden, and then England in the middle of the century.

After the great smallpox epidemic in the 1870s, vaccination became compulsory in most other European countries, and finally also in Spain in 1903. Belgium, together with Austria, was the only European country where vaccination was not made mandatory.

This exceptional situation did not go unnoticed abroad. The leading medical journal The Lancet wrote in 1889 that the anti-vaccination movement hardly needed to campaign here because “indifferentism, which is peculiarly rife in Belgium, seems to answer its purpose”. Medical experts tried to convince the general public of compulsory vaccination, but “it is very doubtful if they will get many people to listen to good advice”.

The reality had little to do with national character. Rather, the young Belgian nation did not want to impose strict rules on its inhabitants. In political circles, compulsory vaccination was seen as a major restriction on individual freedom, despite the country’s higher smallpox mortality rate. The effectiveness of the vaccine was also called into question. In the meantime, it became apparent that several doses were required to achieve lifelong immunity.

In 1911, a draft law on compulsory vaccination was submitted to parliament, but it was not presented again until decades later due to elections, war conditions and other developments. Mandatory vaccination was eventually introduced in 1946, at a time when there were no more victims but vaccination was still necessary to prevent the return of smallpox.

If you want to use one of the dataset mentioned above, do not hesitate to contact queteletcenter@ugent.be.

Or would you like to lend a hand to our new citizen science project www.sosantwerpen.be in which we will study the social inequalities in causes-of-death in the city of Antwerp (1820-1946) with the help of volunteers ?

Do you want to know who the victims of the cholera epidemic were in Antwerp? Then register via sosantwerpen@ugent.be

Sources

- UGent Quetelet Center, HISSTER database.

- Draft Health Bill 1911, Chamber of Representatives, 5 December 1911.

- Proposed Dexters Bill, Chamber of Representatives, 7 August 1945.

- Royal Decree on cowpox vaccination, 6 February 1946.

Literature

- Devos, Isabelle. “De negentiende-eeuwse antivaxers”. De Standaard, 23 december 2020.

- Gadeyne, Guy. “Maatregelen ter bevordering van de vaccinatie uitgevaardigd door het Centraal Bestuur van het Scheldedepartement (1800-1814)”. Annalen van de Geschied- en Oudheidkundige Kring van Ronse, 23 (1973): 133-171.

- Gadeyne, Guy. “Variolatie en vaccinatie tegen de pokken in België sinds de 18de eeuw”. Geschiedenis der Geneeskunde 6, nr. 6 (2000): 364-375.

- S.N., “Smallpox and vaccination in Belgium”. The Lancet 133, nr. 3430 (1889): 1048