Auteur: Patrick Deboosere, demographer at the VUB’s Interface Demography.

(Only available in Dutch)

De oversterfte door Covid-19 heeft van april 2020 de dodelijkste aprilmaand gemaakt sinds de Tweede Wereldoorlog. Zonder de drastische maatregelen die we intussen allemaal kennen zouden de cijfers zelfs nog flink stuk hoger opgelopen zijn.

Covid-19 is net als griep een virale aandoening. Een vergelijking is dus niet zo gek. De Spaanse griep van 1918-1919 geldt dan vaak als referentie. Aan die epidemie stierven in ons land naar schatting ongeveer 30.000 mensen. Vaak ook jonge mensen. Achteraf bleken sterftecijfers heel sterk te verschillen tussen steden waar quarantainemaatregelen werden genomen en plaatsen waar niets werd gedaan.

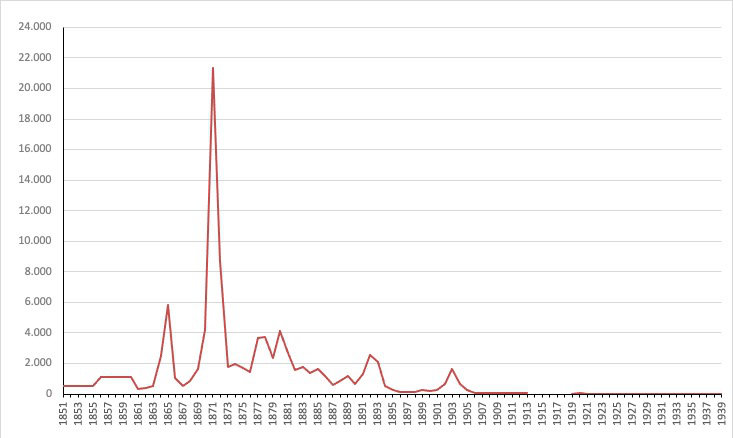

Maar niet enkel de Spaanse griep kostte veel mensenlevens. Bij vrijwel iedere griepepidemie kunnen we de verhoogde sterfte registreren. Ook in België is dit het geval.

In recente jaren is aldus gebleken dat verschillende griepepidemieën door ons land zijn getrokken en een spoor aan oversterfte hebben nagelaten. De meest recente golf van griepgebonden oversterfte in België werd opgetekend tussen eind februari en de eerste helft van maart 2018. Ook in januari 2017 was er een kortstondige episode van lichte oversterfte en wat verder terug in de tijd, in februari 2015, was er al een grote oversterfte vastgesteld.

Het is pas recent dat we in Europa binnen verschillende landen dagelijks de sterfte opvolgen en gebruiken om gezondheidscrisissen op te sporen en daar lessen uit te trekken. Een griepuitbraak in vroegere tijden werd dus pas wat later vastgesteld. In tegenstelling tot vandaag kon men de schaal ervan niet meteen opmeten en inschatten. Dat valt goed af te lezen uit de verslaggeving in kranten uit die tijd.

Historisch werden een aantal wereldwijde griepepidemieën als heel bedreigend ervaren en deze zijn dan ook in het collectieve geheugen gegrift. De meest bekende zijn de Aziatische griep van 1957-58 die naar schatting wereldwijd een miljoen mensen het leven zou hebben gekost, de Hong-Konggriep in 1968-69 en de Mexicaanse griep in 2009. Voor 1957-58 merken we in België inderdaad een langdurige periode van oversterfte die start in oktober 1957 en zal aanhouden tot april 1958. Er is geen sprake van een echte piek, maar van maandenlange hoge sterftecijfers. Ook de Hongkonggriep laat in januari-februari 1968 een piekmoment zien. De Mexicaanse griep van zijn kant lijkt in België weinig impact te hebben op de sterfte.

Maar er zijn ook de vergeten epidemieën. Zo hebben we in België twee wintermaanden meegemaakt waarbij de absolute sterftecijfers hoger waren dan de piek die covid-19 in april 2020 heeft veroorzaakt. Het gaat om januari 1951 met 15.399 overlijdens en februari 1960 met 15.425 overlijdens. Gegeven dat de Belgische bevolking kleiner was dan vandaag zijn de bruto sterftecijfers voor die twee maanden hoger dan deze van april 2020, omgerekend naar jaarbasis ongeveer 21 overlijdens op 1000 personen tegenover 16 in april 2020.

Op 13 januari 1951 wordt in de Belgische pers melding gemaakt van een “vreselijke griepepidemie in Noord-Engeland”, de zwaarste sinds de griepepidemie van 1918. De “doodgraversploegen moeten worden versterkt” en de economie lijdt onder de massale ziekte. De Gazet van Antwerpen van 16 januari 1951 schrijft dat de griepepidemie volgens de Wereldgezondheidsorganisatie oprukt in twee kolonnes. Er is een infectiehaard in Noord-Spanje en een andere in Zweden. Maar, “de tijdens de oorlog ontdekte sulfamieden en antibiotica” zullen het mogelijk maken “secondaire infecties die de meeste slachtoffers hebben gemaakt tijdens de epidemie van 1918, suksesvol te bestrijden.” De dag voordien had de Gazet van Antwerpen op haar voorpagina ook al over de griepepidemie bericht onder de titel “Belgen bieden hardnekkig weerstand” (GvA 15/1/1951). “Sommige buitenlandse bladen publiceren fantastische berichten over de griep-epidemie in België. Lazen wij niet dat ongeveer 1/3 der Belgische bevolking bedlegerig zou zijn!… God zij dank, zo’n vaart neemt het niet! Ofschoon wij nog niet in het bezit konden komen van officiële statistieken, blijkt het dat de ziekte thans stationnair is en in sommige streken zelfs terugloopt. De bevolking biedt prachtig weerstand. – weerstand die voornamelijk te danken is aan de goede voeding. Zo nochtans de sterfgevallen toenemen, dan is dit niets ongewoons, vermits het sterftecijfer elk jaar stijgt in de wintermaanden.”

Wanneer de Gazet van Antwerpen diezelfde maand (27/1/1951) nog over de griep bericht is het om te verwijzen naar Engeland waar de week voordien 1.099 personen aan de griep zijn gestorven en hoe overal ter wereld schepen uit Engeland in quarantaine werden geplaatst.

Terwijl de griep van 1951 wereldnieuws was omwille van het dodelijk karakter, lijkt het dat de griep in 1960 eerder als ongevaarlijk werd gezien. De Gazet van Antwerpen zal in februari 1960 in meer dan 100 artikels naar de griep verwijzen. Maar de toon is geruststellend. Op 9 februari 1960 titelt de krant op de voorpagina “Veel zieken, maar geen griepepidemie in ons land”. En het artikel stelt “Men mag niet van een griepepidemie in België spreken. Al heerst de ziekte vrijwel overal, zo is het aantal aangetaste personen toch zeer veranderlijk volgens de streken en nergens boezemt zij levendige ongerustheid in. Voorts worden vooral volwassenen door de griep getroffen. Geen enkele school schijnt haar deuren te hebben moeten sluiten, ofschoon de griep van 1960 een kenmerkend sterk besmettelijk karakter heeft, dat haar enigszins op hetzelfde niveau als de epidemische ziekten plaatst. (…) Uit de verklaringen van de zieken en van de overwerkte geneesheren die de duizenden zieken verzorgd hebben, mag men besluiten dat de griepverschijnselen – een griep die dit jaar typisch Belgisch lijkt te zijn, daar zij naar verluidt minder erg is dan de griep die in de overige Europese landen heerst – de volgende zijn: hoofdpijn, rillingen, koorts en algemene vermoeienis. Met sulfamiden en vitaminen C is men de griep spoedig de baas.”

De volgende dagen zal de krant ook vol staan met reclameboodschappen over de griep. “Het staat thans vast, dat de griep 1960 in werkelijkheid niet gevaarlijk is. Ze wijkt voor een doorgedreven behandeling met “ASPRO”, 2 tabletten om de 3 uur, en warme dranken.” (20 februari 1960) De werkelijkheid was echter grimmiger, alleen waren de tijdsgenoten zich er niet van bewust.

Sources:

- Data: UGent Quetelet Center, Hisster database.

- Quotations: Gazet van Antwerpen, Digital archive.