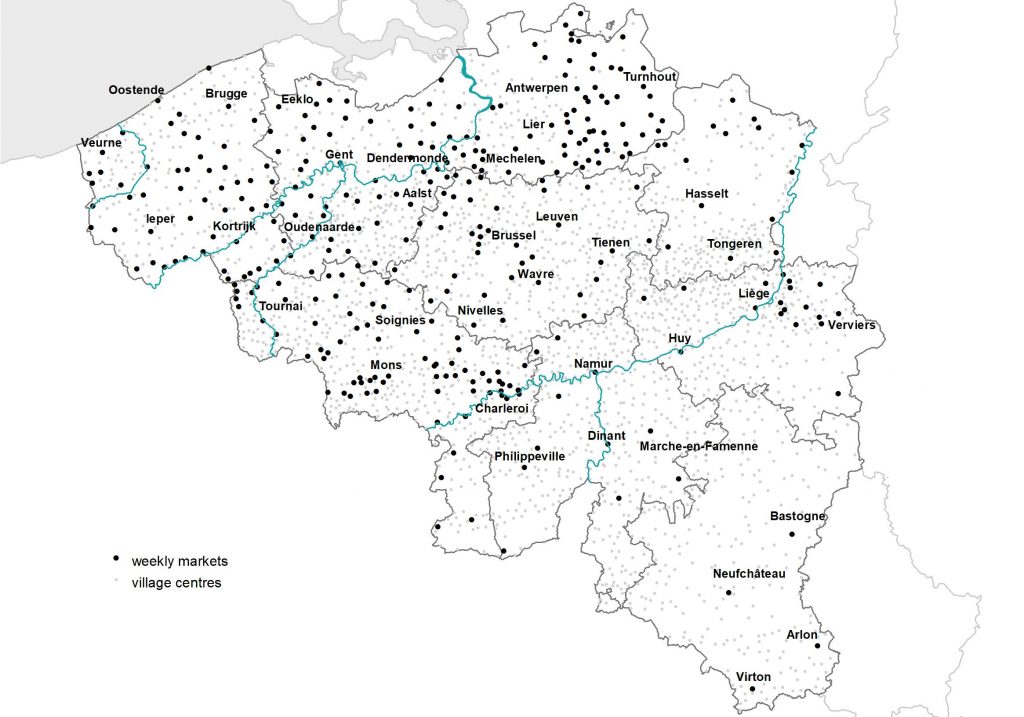

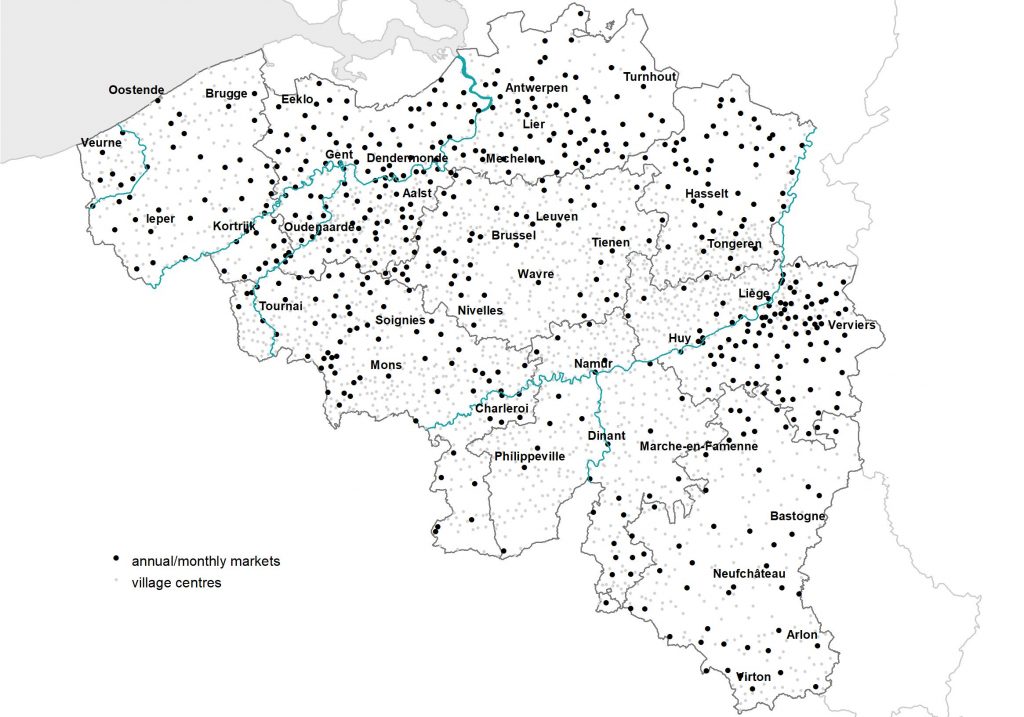

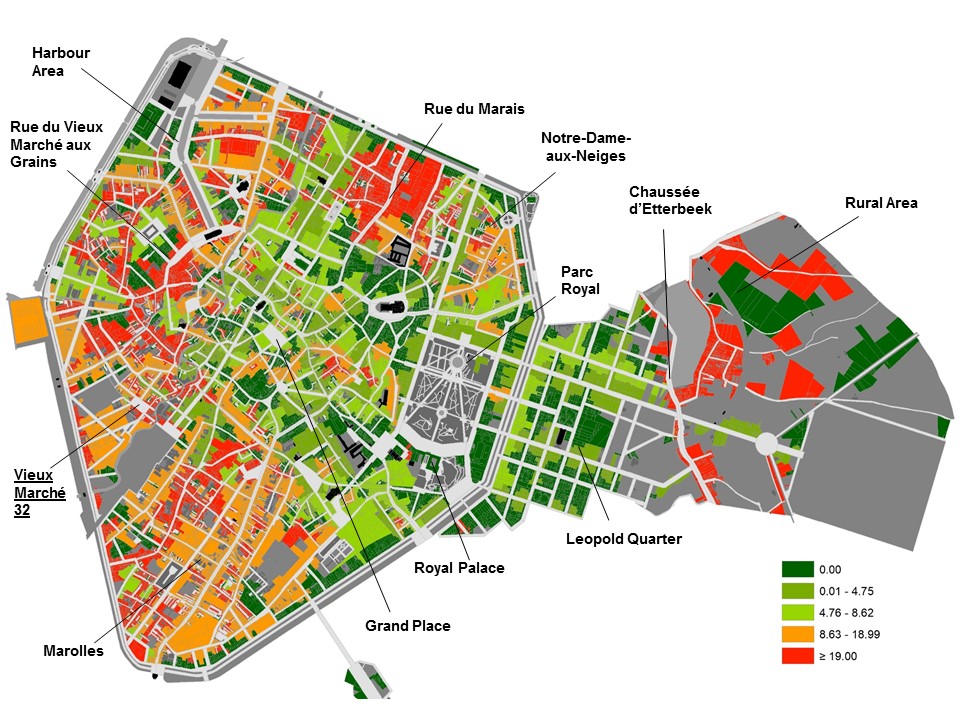

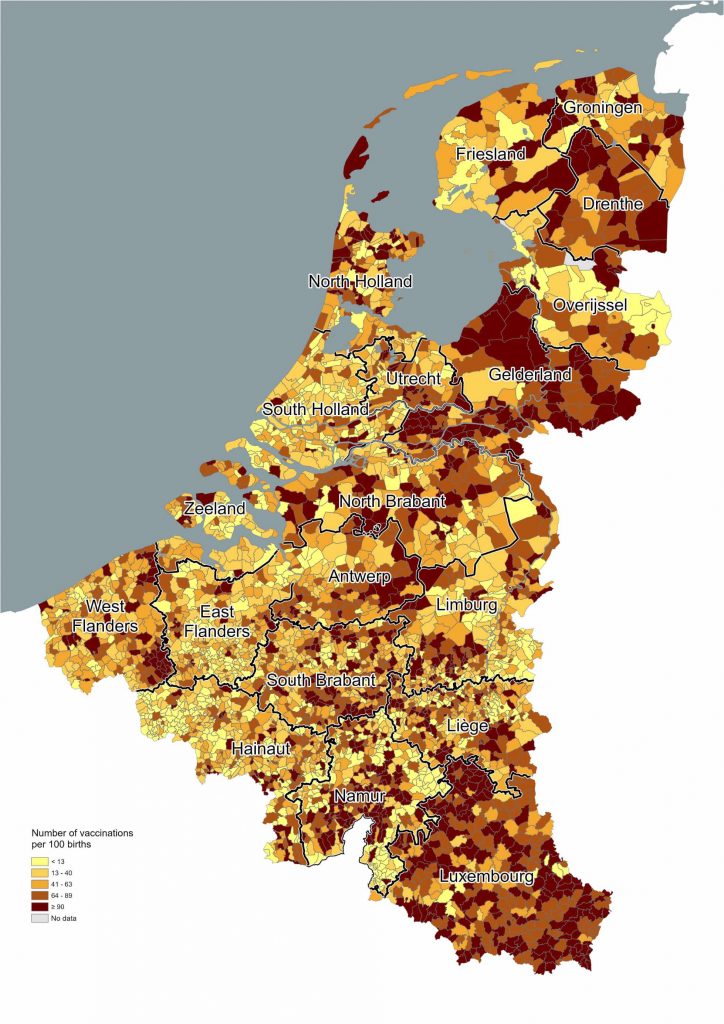

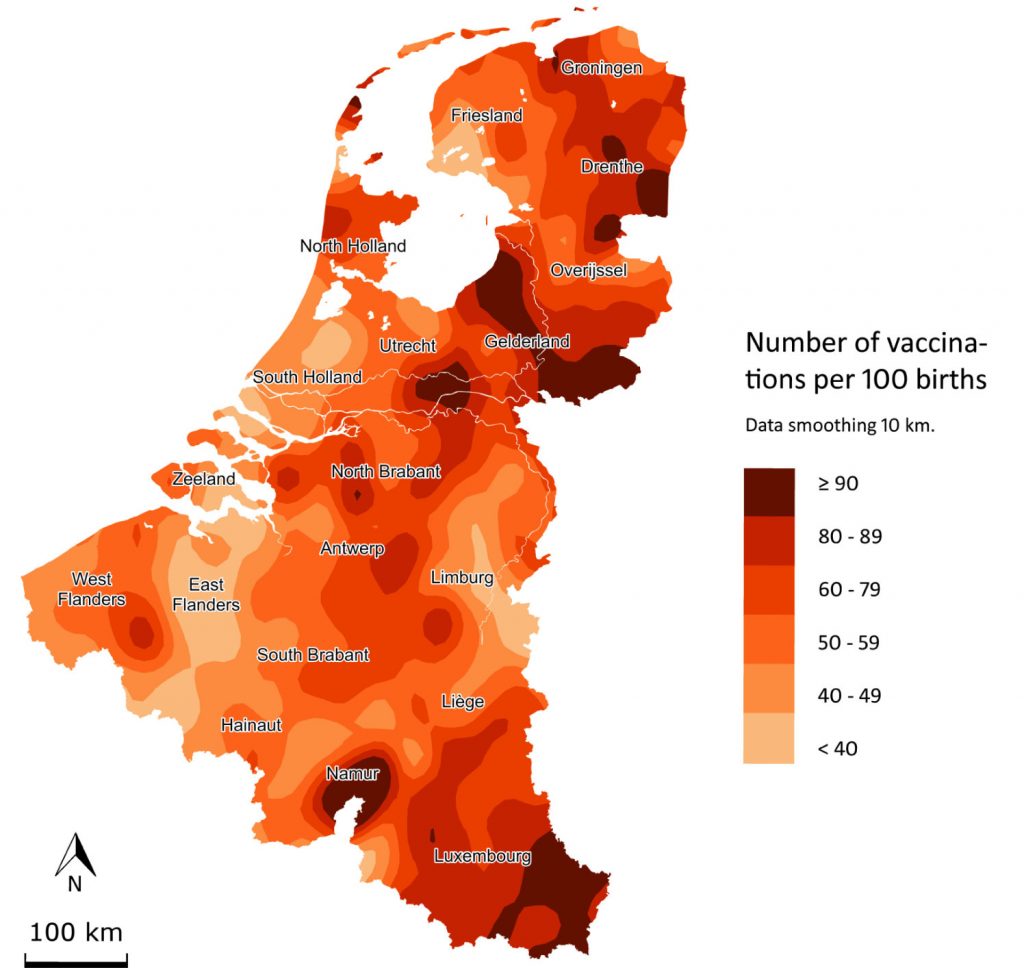

The maps immediately make it clear that there were enormous regional differences in Belgium. This is primarily, but not exclusively, due to settlement patterns and population density. Obviously, more markets can be found in areas where the land is divided into many small villages than in areas with only a few sprawling villages. This was the case, for example, in East Flanders and West Flanders, where there were many weekly markets, but not in Haspengouw, where nevertheless there were also many small municipalities. Furthermore, there were many markets in the densely populated, emerging Walloon industrial areas around Mons, La Louvière, Charleroi and to a lesser extent Liège, though also in the much less densely populated Antwerp Campine almost all municipalities had a market. South of the Sambre and Meuse rivers, where few people lived, there were also few markets.

The map for 1868 further reveals that, in addition to settlement patterns and population density, regional economic differences also played a role. The many weekly markets in the Antwerp Campine mainly served to allow local farmers to sell their butter, destined for the big cities among other places, at advantageous prices, whereas the markets in the Walloon industrial areas were probably mainly intended to ensure supplies to local consumers. Annual markets, which in the nineteenth century still played a role in the cattle trade, were remarkably common in the pasturelands around Liège, among other places.

Finally, there are also traces of the power that cities were long able to exercise over nearby rural areas. For example, there are remarkably few markets in the immediate surroundings of a few large cities such as Bruges, Ghent, Antwerp and Brussels. Nevertheless, there were already markets in some municipalities that bordered on those large cities and which were probably already part of the urban agglomeration, such as Borgerhout near Antwerp as well as Schaarbeek and Sint-Jans-Molenbeek near Brussels.

The struggles, physical and verbal, that have been waged over the centuries in and around markets clearly show the importance of this institution. The right to hold markets was contested between urban and rural areas. Buyers and sellers, men and women, farmers, vendors, craftsmen and shopkeepers all fought for access to markets. Markets provided access to and control over trade flows, a direct source of income for sellers, sometimes indirectly for the shopkeepers and innkeepers who welcomed more people on market days, and for authorities that collected taxes at markets. Knowledge of the development of these specific markets is essential for a good understanding of daily life in the past.